Although it might seem to be a clear-cut issue, the question of clerical celibacy is anything but simple. Although celibacy is not explicitly encoded in church dogma,[1] it is firmly rooted in Church tradition. As Anthony Towey writes, “sometimes imagined to be a medieval invention, the tradition of celibacy is easily connected to the Gospel tradition.”[2]

Pope Francis says that something is a tradition “only if it grows” and that it has to grow in the same direction as its roots.[3] These words were taken as a possible opening to changing the rules on clerical celibacy. However, he has also said, in line with his predecessors Paul VI, John Paul II and Benedict XVI, that “it is my own personal decision, I will not do it, let this be clear … I am not willing to go before God with such a decision.”[4]

In this essay we shall examine whether the removal of compulsory clerical celibacy in the (Latin side of the) Catholic Church is possible and desirable. We shall look at the historical, theological, customary and practical reasons adduced by parties on either side of the issue before seeking a dialectical synthesis in our conclusions.

The “Holy Orders is the sacrament through which the mission entrusted by Christ to his apostles continues to be exercised in the Church until the end of time: thus it is the sacrament of apostolic ministry. It includes three degrees: episcopate, presbyterate, and diaconate.”[5] Hence it is one of the seven “traditional” sacraments of the Catholic Church, although the modern reading of sacraments is wider in scope and we can say nowadays that “the Church itself is the core sacrament, as Christ is himself the sacrament of God.”[6]

This reading might also help in understanding why celibacy is a very important issue for some, as the potential change to the rules governing ministry strikes very close to the core of what the Church is. “The Catholic Church is the oldest institution in the Western world, tracing its history back almost 2,000 years, and counts more than a billion members.”[7] It is therefore an organization where tradition is highly valued and thus plays an extremely important role. Furthermore, some of these traditions are traced back to Jesus and hence to God himself. This occasionally hampers dialogue when one side thinks the Bible supports a certain point of view whilst the other believes it supports the opposite.

In the Catholic Church there are already married priests, mostly from the thirteen Eastern rites but there are also former Anglicans who have become Catholics. There have been Anglicans turned Catholics since about 1956, when Pius XII allowed this to happen. In 2009, Pope Benedict XVI promulgated the Apostolic Constitution Anglicanorum Coetibus that allowed entire groups of Anglicans – and later from other Christian communions too – to become Catholic[8] with their own set of prayers and liturgy, forming a new de facto modern rite. Some other Latin churches, practicing other rites, such as the Ambrosian rite, included married priests until about the time of the Council of Trent. It thus seems that celibacy is a question of usage and custom.

As the current Secretary of State of the Holy See, Pietro Parolin, said in 2013, priestly celibacy is “an ecclesiastical tradition that can be discussed”.[9] Harris and other authors point to the fact that it was introduced (also) to deal with the problem of heirs of priests who claimed properties that might otherwise have belonged to the Church, or made it difficult for the Church to take possession of them.[10] Hence they link this change to compulsory celibacy – which happened in the twelfth century and was then codified into law at the Council of Trent – to “a practical suspicion that Church property might be dissipated by the inheritance claims of clergy children.”[11] Others consider that, in the modern day, supporting a priest with a family would cost more and this might mean that the priest would have to have another job, taking time away from his pastoral mission, or that the Church would have to support him and his family, spending more than it does nowadays for celibate priests.[12]

Since Paul VI wrote the encyclical Sacerdotalis Caelibatus,[13] a lot of historical research has been done on celibacy in the early centuries of the church. It appears that the roots of priestly celibacy go back to the beginning of Christianity: it is probable that Jesus summoned married men as his apostles (apart from John, the youngest, who was celibate), as it was the custom among Jews to marry young; we know for certain that Peter was married. However, it appears that the apostles had to leave their families behind to follow Jesus (Luke 18, 29-30). In addition, from his epistles in the New Testament, we know that Paul of Tarsus, the most famous missionary of early Christianity, held the view that celibacy was the better option for all Christians and not only for Church leaders. He himself had probably been married but was living a celibate life.[14] Also, in the first two or three centuries of Christianity, with “the development of monasticism, the esteem held for virginity and the lifestyle choices of influential figures such as Basil, [Ambrose, Jerome], Augustine and others, cemented the ideal of celibacy as the preferred clerical state”.[15]

Nevertheless, on this point too there is disagreement: Casali objects that there are “no theological reasons” and adds “nor a consolidated praxis” as celibacy “affects less than half of the history of Christianity, and only those of Latin Rite. What is more, with some exceptions”.[16] He also points out that celibacy does not exists for the other Abrahamic religions: both imams and rabbis can marry, as can priests in Protestant and Orthodox Christian churches.[17] The late Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini, Archbishop of Milan, pointed out that priests can marry in all Churches except for the Roman Catholic Church and, importantly, he adds “The idea that priests should not marry comes from monasticism.”[18] Those who support the end of compulsory celibacy see it as a way to have more priests on continents, such as Europe and the Americas, where the number of seminarists is constantly declining.[19]

On the other hand, those who support celibacy believe that it is the Eastern Churches that have moved away from the teaching of the Apostles. They point to the early history of the Church: in a canon of an African Council of 390, a reference is made to a “perfect chastity” needed to perform priestly duties, dating it back to the time of the Apostles. This canon was important because others, later on, referred to it in order to take decisions on the matter. The first to make a reference to it were the Byzantine Fathers in the Council of Trullo 692 AD; in the modern era it was Pius XI with the encyclical Ad catholici sacerdotii fastigium (1935). Alongside this Canon of Cartago, there are public documents that trace the absolute continence of priests back to the times of the Apostles. One such document is the Decretal Directa (10 February 385) that Pope Siriacus sent to Imerus, Bishop of Terragon (Spain), in which he wrote of the duty of “perfect continence” from the day of ordination. Two other Decretals, Cum in unum (386) and Dominus inter (a few years later) record that chastity for priests is again prescribed, linking it back to the Apostles and Biblical passages. Other writings of that era held the same view, such as the Panarion by Bishop Epiphanius of Salamis (about 311–403), the Ambrosiaster, and others by other Fathers of the Church mentioned in the second page of this essay.[20]

In the current times, Pope Francis has stated that celibacy is a gift, a grace that characterises the Latin Church, and confirms: “it is a grace, not a limit”.[21]

Over a dozen years ago, Carlo Maria Martini wrote about viri probati; he tried to sell the idea to others as a way to tackle the problem in some parts of the world of having too few priests who had to serve more than one parish at the same time.[22] The idea of viri probati was discussed at the recent synod on the Amazon (2019) and “[u]nder the synod’s proposal, passed by 128 votes to 41, married ‘men of proven virtue’ could join the priesthood in remote parts of the region.”[23] However Pope Francis was not keen to officially grant this exception to celibacy. At present, the Church is probably heading for a situation where some selected mature deacons will be promoted to the presbyterate after undergoing up to three years of training.

It is interesting to note that in early 2020, while the world was waiting for Pope Francis’s decision on this issue, it was rendered public that Cardinal Sarah, together with Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, had written a book due to be released soon on the topic of priestly celibacy and that their position was for the status quo. One day before the book was to be on the bookshelves, Benedict XVI requested to have his name removed from the book cover; of course this only helped publicize the book and the views it expresses.[24]

This paper has shown that the issue of compulsory celibacy is one that can be discussed, as it is not a matter of faith. Whether it is desirable is a matter of opinion and here the (Latin) Church is divided: we can foresee that the topic will be discussed at future synods[25] or perhaps even in a future Ecumenical Council, since such a radical change will probably have to be a collegial decision by the Church a not by the Pope alone.

Short essay by: Volfango Rizzi

Copyreader: Robert Burns (ceresetta@libero.it)

[1] As confirmed in 2013 by the Archbishop Pietro Parolin – now Secretary of State of the Holy See, Cardinal Bishop and member of the Council of Cardinals – in an interview with the Venezuelan daily newspaper El Universal (see article by Peloso).

[2] Towey (2018): 276.

[3] Agasso, article on La Stampa, 4th February 2020.

[4] Buscemi & Cardinale 2020.

[5] Catechism of the Catholic Church: 1536.

[6] Guzie, Tad in Hayes & Gearon (1998): 434.

[7] BBC, article 27th October 2019 “Catholic bishops back limited relaxation of celibacy rule”.

[8] Pope Benedict XVI (2009).

[9] Peloso (2013), Il successore di Bertone apre su celibato e democrazia, article online.

[10] Harris (2019): 28.

[11] Towey (2018): 277.

[12] Casali, Il celibato dei preti, article online.

[13] Pope Paul VI (1967).

[14] Some hold the view that Paul was a widower, other think that he had repudiated (divorced) his wife.

[15] Towey (2018): 277.

[16] Casali, Il celibato dei preti, article online.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Martini, Carlo Maria & Sporshill, Georg 2008: 32.

[19] The Holy See Press Office advises us that in the 5 years between 2013 and 2018 Europe registered a contraction of -15.6% and the Americas of -9.4%.

[20] On the contrary the Pastoral epistles contained in the New Testament mention married bishops, presbyters and deacons (1Tim 3:2-5; 1Tim 3:12; Titus 1: 5-6).

[21] Agasso, in La Stampa 4th February 2020.

[22] Martini, Carlo Maria & Sporshill, Georg 2008: 100.

[23] BBC, article 27th October 2019 “Catholic bishops back limited relaxation of celibacy rule”.

[24] Socci, Antonio (2020) also see the article by Faro online (2020).

[25] The current synod of the German Church, started with the first session on 30th January – 1st February 2020, intends to discuss compulsory celibacy among other delicate matters such as the ordination of female deacons or deaconesses. See article by Pongratz-Lippitt (2020).

Short essay by: Volfango Rizzi

Copyreader: Robert Burns (ceresetta@libero.it)

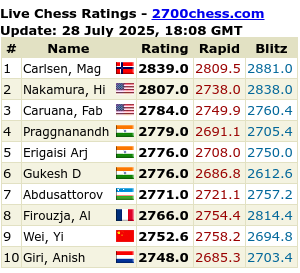

è una rivista bimestrale, che tratta esplicitamente di scacchi, rugby, pugilato e scacchi-pugilato.

Include, inoltre, la rubrica “altro”, in cui, in aggiunta a temi come l’aromaterapia e i giochi, viene offerta la

possibilità di sviluppare, in maniera coinvolgente, vari argomenti d’interesse generale.

è una rivista bimestrale, che tratta esplicitamente di scacchi, rugby, pugilato e scacchi-pugilato.

Include, inoltre, la rubrica “altro”, in cui, in aggiunta a temi come l’aromaterapia e i giochi, viene offerta la

possibilità di sviluppare, in maniera coinvolgente, vari argomenti d’interesse generale.

COMMENTI RECENTI