The base on planet Terra warns me: “landing in eleven minutes.” I still have some time to prepare myself psychologically for my arrival and also to reflect on the very long period spent either travelling through space or residing on the space station. I left Earth in 2020 when I was 22 and had just finished a Master’s degree in Engineering Physics. It is now 2250 and I am returning “home”: I will not have any family or relations left and I am curious to see, first hand, how civilisation has developed in the last 230 years.

Forty days have passed since my return to our planet. Most of my time has been spent trying to readjust to life on earth in a military hospital, where I am writing this. I have had virtually no occasion to go round the town, except in the last few days. I have, however, discovered a lot about contemporary life by watching videos on strange screens that must be the offspring of the television sets I once knew. What has amazed me the most, so far, is seeing how important and widespread the Catholic Church has become, so when I manage to mingle with some people, I curiously ask them how this had happened.

I left whilst Pope Francis was the head of the Roman Catholic communion. I was told that his successor, who was a relatively young Cardinal when he was elected to the See of St Peter, soon convoked an Ecumenical Council. He wanted this new Council – the 22nd in history recognised by the Catholic Church – to be Universal. Besides Catholic bishops, the invitation was also extended to the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, the Anglicans, the Old Catholic Church, the Anglo-Catholics, the Assyrian Church of the East, the Lutheran Churches, the Moravian Church[1] and other protestant churches such as the Methodists and even the Christian Unitarian Universalists.

I left whilst Pope Francis was the head of the Roman Catholic communion. I was told that his successor, who was a relatively young Cardinal when he was elected to the See of St Peter, soon convoked an Ecumenical Council. He wanted this new Council – the 22nd in history recognised by the Catholic Church – to be Universal. Besides Catholic bishops, the invitation was also extended to the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, the Anglicans, the Old Catholic Church, the Anglo-Catholics, the Assyrian Church of the East, the Lutheran Churches, the Moravian Church[1] and other protestant churches such as the Methodists and even the Christian Unitarian Universalists.

This opening had been carefully prepared over the years. In previous years, the Vatican approached the Moravian Church in Europe, a protestant church that still retained the episcopal order, offering them the use of one of the Catholic seminaries in Germany to train their ministers. The Moravians had not had a seminary in Europe since 1947.[2] A similar proposal was made to other small protestant churches lacking means to train their own clergy in a proper seminary. Eventually a few Catholic-other Christian communions “joint-seminaries” were established in some European countries. Some Anglican bishops around the world also took up the offer to join efforts in training the clergy.

Meanwhile, dialogue[3] and the number of ecumenical conferences and even joint Eucharistic celebrations[4] were increased at the central and local levels. Similarly, the Church continued on the path of inter-religious dialogue, particularly reviving its Jewish roots and establishing the best relationship it had ever had with Judaism. On top of this, the Church continued to ask forgiveness for its past persecutions of other Christians, such as the Waldenses.[5] Similarly the Church asked for pardon from brothers of the Muslim faith for the various wars of conquest in the past centuries.

At the same time, a more collegial approach was taken to Church management, with important decisions taken by the College of Bishops and not by the Pope alone. Continuing the path of democratisation initiated by Pope Francis, his successor continued to choose Cardinals from among the ranks of those who had been elected President or Vice-President by the Episcopal Conferences, and no longer those who had become bishops or archbishops of historically important metropolitan dioceses.[6] This has now become a rule and not a line of conduct adopted by one particular pope.

At the proclamation of the New Universal Ecumenical Council, the Pope clearly mentioned that his intention was to drop the dogma of infallibility, but that it would have been the Council to decide on this, also deciding on the doctrine of papal primacy. This was an excellent move to attract a great number of bishops belonging to the Orthodox Churches[7], as well as the Old Catholics, to the Council.[8] And in fact many of them attended, as did the Anglicans, the Moravians and the representatives of over two hundred churches out of three hundred and fifty that belonged to the World Council of Churches.[9] As this was pretty much the first Universal Council that Christianity had had in over a millennium, most of the Churches around the world considered it both significant and legitimate.

Here are some of the decisions to modernise the church taken in this Council: the Pope was no longer considered infallible on matters of faith, the Ecumenical Council was granted authority over all bishops, including the Bishop of Rome, women were allowed to the diaconate, priesthood, and the episcopate,[10] both men and women in the clergy were allowed to marry.[11] Bishops could marry, and even be parents, the only limitation being that the children had to be of age before the parent could be appointed bishop.

To accommodate the new groups into the universal Church, new rites were allowed in parts of the world, as were new liturgies, similarly to what had happened with the Divine Worship of the Ordinariates.[12] Churches around the world were no longer obliged to follow the Roman rite but could choose among other existing ones, such as the Ambrosian rite.

There was even more freedom to accommodate local customs into liturgies and more willingness of the local Christian communities to make changes, thus rendering the instructions contained in Liturgiam Authenticam something of the past. This allowed forms of syncretism in some areas, which permit Christians to celebrate liturgies together with both worshippers of ancient religions and with new-age types of beliefs. In some parts of the world, you may enter a church and witness a kirtan performance while also discovering Christian hymns among the songs. Hence churches have become places where people, even from different religions, can have a place of worship and mystical communion with the Almighty or the universe.

There are now strong local differences in worship and customs.[13] How different this is from the time when the mass was conducted in Latin, the presbyters where facing the tabernacle and it was pretty much the same everywhere! Moreover, laymen and laywomen now take important roles during the celebrations: they sing, offer communion to their fellows and also preach and comment on the word of God.

I remember the time when the Catholic Church, at least in Europe, was left with a few old priests. Now, the possibility of having a family has allowed more people to follow their vocation and serve the Christian community. Allowing women to join the holy orders has resulted in a surprising number of new deacons and presbyters. Indeed, in many parts of the world, most priests are women.

The Synod of Bishops (in which some representatives of the laity are included too) passed from being mostly a consultative body for the Pope to being a decision-making body. The change was strongly advocated starting from the 16th Ordinary General Assembly, convoked by Pope Francis.[14]

Synodality is used not only at the top level, with the College of Bishops taking the principal decisions, but is also applied at the local, regional and national levels. At the national level there still are Episcopal Conferences (these too reserve a space for representatives of the laity) whose voices are strongly heard, and considered, by the College. But even at the diocesan and parish levels there are synods in which the laity (who are the majority) and clergy meet to take decisions and to explore paths to the future for the local parish and diocese.[15]

Hence the Congregation for Bishops, which oversees the selection of at least 96% of bishops, selecting the top three names to pass to the Pope (who chooses one of them), has to take parish-level elections into account in dioceses that have a vacant episcopal post, to ascertain if there is a strong candidate wanted by the people at the local level. This is a middle way from early Christianity when the local community elected its bishop. Similarly, the Congregation takes into consideration any recommendation that the National Episcopal Conference gives about members of the clergy that show aptitude for the episcopate. Only four percent of all new bishops can be chosen by the Pope alone, if he or she so wished, and these tend to be within the Roman Ecclesiastic Province and few other dioceses directly linked to the Vatican.

Even the way bishops are consecrated is somewhat different, as the Pope is not usually involved in the ordination. The new bishop is ordained by three bishops, usually of the same National Episcopal Conference. The Pope still creates Cardinals, but these have lost part of their prestige and are seen more as helpers and advisers to the Pope (as the College of Cardinals)[16] and as potential electors of the future Pope (in a Conclave).[17] What is different now is that they cease to be Cardinals or electors once they reach the age of 80. No more than one hundred twenty Cardinals can enter the Conclave. If there are more than that in the Vatican at the time of a Conclave, the one hundred-twenty eldest will be selected to enter the Conclave; of course those left out are still eligible to become the new Bishop of Rome.[18]

If I had to compare this system of government to that of states, I would say that the Papacy resembles the Presidency,[19] the College of Cardinals the government (day-to-day operations and decision-taking), and the College of Bishops would be similar to Parliament, which decides the general direction to be followed. The use of the subsidiarity principle echoes what happens in many federal countries.[20]

With the role of the Pope somewhat reduced and that of the College of Bishops enhanced (from a mostly consultative body to a decision-making body), with laity engaged in taking decisions at all levels (as a majority at the parish and diocesan levels), with holy orders open to women too, and with more young pastors (some with direct experience of family life), the Church seems more than ever to be made in the image of the People of God and well equipped to carry out its role as the sacrament of Christ.[21]

A tale by Volfango Rizzi

Copyreader: Robert Burns (ceresetta@libero.it)

[1] The Moravian Church, or Unitas Fratrum, has it roots in the 15th century, before the Protestant Revolution, and has contacts with the Waldenses (see Note 2); it has the peculiarity, among the Protestant churches, of retaining bishops, although they do not have an administrative role.

[2] There are only two places in the world where one could train to become a minister of the Moravian Church: the Moravian Seminary in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania and at Teofilo Kisanji University in Tanzania, the country where this Church has most believers.

[3] Dialogue among the Catholic and other Churches is happening all the time. Particularly important is dialogue between the Catholic and the Orthodox Churches. Here, an important issue is the question of the primacy of the Bishop of Rome. See article by the Archdiocese of Baltimore.

[4] Until the Second Vatican Council “The Catholic Church officially was not interested in ecumenism”, Thomas Raush in Hayes & Gearon (1998): 260.

[5] Or “Waldensians”, among the first movements that broke with the Roman Church, centuries before the Protestant Revolution. They had to bear centuries of harassment, persecutions and even executions. In Harris (2019): 17, the Albigensians are mentioned as a threat to the Church: the Waldenses were thriving in similar geographical areas and in similar times (the beginnings of the Waldenses date back to the 12th century).

[6] Piero Schiavazzi (2019) article on both huffingtonpost.it and Limesonline.

[7] “The expansion of papal authority reached its climax in 1870 at the First Vatican Council, which proclaimed the doctrine of papal infallibility and anathematized, that is, cast out of the Church, all who refused to recognize papal supremacy.” This exacerbated divisions between the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Churches, both Eastern and Oriental.

[8] Some bishops and faithful broke with Rome following the dogma of Pope Infallibility. Most of these churches are federated in the Union of Utrecht of the Old Catholic Churches, but in some countries, where the presence of the Old Catholic was not great, or where there have been divisions, the members of these churches have merged with other groups, such as the Anglicans (which, by the way, is in full communion since 1931). For instance, in Italy parishes ended up under the jurisdiction of either the Diocese of the Church of England in Europe or the Episcopal Church (United States).

[9] “The WCC is a fellowship of 350 member churches who together represent more than half a billion Christians around the world.” World Council of Churches.

[10] “The Church has always maintained that through baptism all the faithful share in the common priesthood of Christ.” Richards (2002): 82; and then there is the ordained clergy: bishops, priests and deacons.

[11] “Clerical celibacy began to be enforced as part of the Gregorian Reform” Harris (2019): 18. Pope Gregory II “took canonical measures to enforce celibacy in 1074”: Towey (2018): 277.

[12] In 2009 Pope Benedict XVI, by motu proprio, issued the Anglicanorum Coetibus, a constitution that allowed the formation of “Personal Ordinariates” for those groups of Anglican who wished to become Roman Catholic. Between 2011 and 2012, three Ordinariates where established: one for England and Wales, one for the USA and Canada and one for Australia and Japan.

[13] This is the concept of “Pluralism” through which “a greater diversity of practice in the living-out of the Catholic way of life” is allowed to happen. Harris (2019): 26.

[14] It will be held in October 2020 and titled “For a synodal Church: communion, participation and mission”. See press release of The Synod of Bishops and, also, the article by Salvatore Izzo.

[15] How Church structures were set up at the early days of Christianity can be found, in the New Testament, primarily in the Pastoral Letters (Titus and I & II Timothy). Harris (2019): Unit 1.

[16] In 2013 Pope Francis established a “Council of Cardinals” who serve as his most immediate advisers. Number and composition of the Council has been varied, ranging from a maximum of nine to the present six members; nowadays joined by a Secretary and an adjunct secretary, both bishops.

[17] The current process of electing a pope has evolved from Pope Nicholas II’s bull, In nomine Domini, establishing that the Pope should be elected from the College of Cardinals Bishops in 1059. In 1179 Pope Alexander III gives all Cardinals (Bishop, Priests and Deacons) the right to elect the Pope, and it is still so today. Traditionally Cardinals are thought to be helped, in the discernment of electing the Pope, by the intervention of the Holy Spirit.

[18] In origins the Cardinal were the closest helpers of the bishop (and in early Christianity not only Rome had Cardinals but other Sees such as Milan and Ravenna). Nowadays the Cardinals below the age of 80 can participate at the Conclave that elects the new Pope. In other Christian churches there are no cardinals, it is something peculiar to the Catholic Church. At present one remains Cardinal until death, however, as one has retired and is hence no longer a (potential) voter at the Conclave, we could foresee that this “title” can expire as the two tasks come to an end.

[19] On the “beginning of Ecclesiology” and on the theme of the Roman primacy: Kelly (1978): 189-193.

[20] The concept of subsidiarity means that “decisions should be taken at the lowest level of authority” Harris (2019): 26.

[21] In a Church that is welcoming and where one can feel the presence of the Holy Spirit.

A story-tale by Volfango Rizzi

Copyreader: Robert Burns (ceresetta@libero.it)

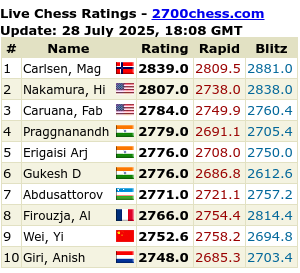

è una rivista bimestrale, che tratta esplicitamente di scacchi, rugby, pugilato e scacchi-pugilato.

Include, inoltre, la rubrica “altro”, in cui, in aggiunta a temi come l’aromaterapia e i giochi, viene offerta la

possibilità di sviluppare, in maniera coinvolgente, vari argomenti d’interesse generale.

è una rivista bimestrale, che tratta esplicitamente di scacchi, rugby, pugilato e scacchi-pugilato.

Include, inoltre, la rubrica “altro”, in cui, in aggiunta a temi come l’aromaterapia e i giochi, viene offerta la

possibilità di sviluppare, in maniera coinvolgente, vari argomenti d’interesse generale.

COMMENTI RECENTI