The importance of Saint Paul on the understanding and development of Christianity has been so great that Clare Richards, in her book, asks: “Does our present Christianity stem from Jesus, or from Paul?”[1] Anthony Towey states that “Paul is the single most controversial figure in the new Testament”[2]; and later calls him “a theological revolutionary”.[3] On top of this Harris states that Paul “launches Christian Theology into the seas of time”.[4] A study of Paul is, therefore, extremely interesting.

Some consider Paul’s writings as misogynist: Alessandro Pascale, in his History of Communism, titles a section: “The misogyny of the Pauline Christianity”, and expands on this view in the main text.[5] Conversely, Towey writes that Paul “is accused of being anti-women, anti-Semitic and even anti-Christian” but adds “unfortunately such views will not be supported in the summary of Paul’s Theology here”.[6] Hence the views on this issue differ considerably.

In this essay we are going to first give a very brief account of Paul’s life in order to highlight why he has been such an important figure in the development of the Christian religion. Secondly we shall make reference to his writings, within the Holy Book, to gain a better understanding of the type of person he was.

In the following section, the main one, we have selected ten different quotes by St. Paul and one by St. Peter to properly address the essay question. We have chosen to quote full verses (sometimes even more than one together) and not short phrases in order to give as much context to the words as possible. These selected quotes will be analysed, in the light of the bibliographical readings, before passing on to dissect additional writings, particularly the epistle to the Romans. We will then draw in other examples and other opinions regarding the issue of being anti-women or, on the contrary, a supporter of women, in reaching our conclusions.

An important element in this essay would be an examination of the role of women in society at the time that Paul was writing. However, due to space constraints, instead of having a specific section on this, we shall deal with this topic whilst developing our argument.

Paulos (as he calls himself in his epistles)[7] “was born to a Jewish family, around the same time as Jesus”[8], or even a dozen or so years later[9], in Tarsus, a city of the Roman Empire that is on the south coast of modern-day Turkey. His parents were probably Roman citizens, and thus so was he,[10] although not all authors agree on this.[11] Although he was initially a Jew who persecuted Christians, some time after Jesus’s death he converted (34-36 AD) and went on to become one of the most fervent Christian missionaries of all time. He figured prominently in giving a direction to a nascent religion. His three or four missions gave him the chance to establish a number of Christian communities and to meet some that were already established, particularly on the fourth one to Crete. In 49 AD he participated in the Council of Jerusalem,[12] the first ever council of the Christian Church. There is no compelling historical evidence of a later journey to Spain or “Europe”, although some believe he did travel there in the years 63-67 before been sentenced to death, and dying a martyr, in Rome in 67-68 AD.

“The outcome of Paul’s mission is extraordinary: he has practically founded the Church in Asia Minor and in Greece.”[13] This quote well summarises the missionary importance of the apostle, and we will discuss his importance in the development of Christian theology later on.

Paul’s writings are contained in the New Testament. They comprise a collection of twenty-seven papers. Paul’s “writings are the earliest” of the New Testament,[14] hence a particular emphasis has been given to them throughout the two millennia of the Christian era. Thirteen letters or “epistles” are attributed to Paul but “scholars disagree regarding which of the letters are indisputably from his hand … Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, 1 Thessalonians and Philemon are rarely questioned …”[15] Other writings range from being considered as mostly written by him but with later additions, written by disciples with or without his supervision, or even written well after his death.

We know about Paul only from his letters and from the Acts of the Apostles (written by his disciple-friend ‘Luke’), both contained in the New Testament. Paul was “keenly aware of himself as a Jew and boasted of his Jewish background, tracing it to descent from Abraham and the tribe of Benjamin … As an Israelite, Paul recognized his privileged status as a member of God’s chosen people”.[16] And again: “Paul also boasted his Pharisaic background…”[17] let us not forget that “Jesus grew up within a Pharisee context”.[18] It does not end here: “though Luke makes Paul assert that he was brought up in Jerusalem and educated at the feet of Gamaliel (Acts 22:3) his letters never give an indication of the influence of Palestinian Judaism.”[19] Reading the New Testament we are told that he was one of the best students in Jerusalem, something we know only from this source and nowhere else.

Boasting appears to be one of his characteristic features and no further historic evidence can be found of the things that he, or Luke, wrote about himself. What is sure is that he never met Christ and, notwithstanding this, he called himself an “apostle”, a designation that was contested in his times[20] but that has become accepted through the centuries. In his first epistle to the Thessalonians (the most ancient of the New Testament), he refers to himself and his colleagues “as apostles of Christ” (1 Thessalonians 2:6). To make sure the point is not lost, in Corinthians he commences the letter in this manner: “Paul, called to be an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God,” while, similarly, he starts his epistle to the Galatians: “Paul, an apostle – sent not from men nor by a man, but by Jesus Christ and God the Father, who raised him from the dead…“.

Reading our Bible, it seems that another way we can see him inflating himself and striving to impress others is found in the passage 1 Thessalonians 3:6; “that ye have a good remembrance of us always and desire greatly to see us as we also desire to see you.“[21] Saying that his ambassador had reported to him that the Thessalonians desired “greatly” to see him and he (simply) desired to see them. Normally one would say the opposite: ‘you desire to see me as I greatly desire to see you’. However, our research reveals that this might be simply an error of translation into various modern western European languages: the difference in degree of desire does not appear in the Latin or, above all, the Greek text.[22]

We have selected some of the most controversial lines of the epistles contained in the New Testament and traditionally attributed to Paul and will briefly comment on them. Some of these consist of more than one verse. Again because of space constraints, the commentary will address several quotes at once.

1) Similarly, women are to wear suitable clothes and to be dressed quietly and modestly, without braided hair or gold and jewellery or expensive clothes; their adornment is to do the good works that are proper for women who claim to be religious. 1 Timothy 2: 9.

2) I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over men; she is to keep silent. For Adam was formed first, then Eve; and Adam was not deceived, but the woman was deceived and became a transgressor. 1 Timothy 2: 12-14.

3) … and show younger women how they should love their husbands and love their children, how they must be sensible and chaste, and how to work in their homes, and be gentle, and obey their husbands, so that the message of God is not disgraced. Titus 2: 4-5.

These are some of the stronger quotations, from the epistles attributed to Paul, on the role and behaviour of women. However, the first and second letter to Timothy and the one to Titus, the so called pastorals, “are very similar in content and style … and, moreover, they are not written by the apostle.”[23] Here we can see our first samples of epistles that the modern exegetes consider as not having been written by Paul but by someone writing around 125 AD, sometimes defined by the scholars as ‘pseudo-Paul’.

4) Wives, be subject to your husbands, as you should in the Lord. Colossians 3: 18.

5) Wives should be subject to their husbands as to the Lord, since, as Christ is head of the Church and saves the whole body, so is a husband the head of his wife; and as the Church is subject to Christ, so should wives be to their husbands, in everything. Ephesians 5: 22-24.

We have put together these two quotes, both focusing on the submission of the wife to her husband. Elisabeth Green agrees with Fiorenza Schüssler that “Ephesians christologically consecrates the inferior position of the wife in the married relationship”.[24] Others also point to the fact that “subordinate” would be a more precise translation than “subject” and that women are compared to the Church and, therefore, that this demonstrates that Paul could not have held a derogatory idea of ‘subordination’.[25] The majority of researchers believe that Ephesians was written by an unknown disciple of Paul between 80 and 90 AD.[26]

As for the epistle to the Colossians, this is also considered to be written in a later period compared to when Paul of Tarsus lived; possibly written by a “chief of a Pauline community of second or third generation”.[27]

However we can see that what is expressed in the above quotations very much reflects the culture of the time in (a great part of) the Roman Empire; in St. Peter’s epistle (1 Peter 3:5) we read: “For in this manner in olden times the holy women also, who trusted in God, adorned themselves, being in subjection unto their own husbands …“. Hence the (real) apostle Peter held similar views to those expressed by Paul or, better, by pseudo-Paul.

We shall now consider additional quotes, all taken from the first epistle to the Corinthians, a Christian community that Paul himself had established.[28]

6) But for a man it is not right to have his head covered, since he is the image of God and reflects God’s glory; but woman is the reflection of man’s glory. 1 Corinthians 11: 7.

7) For man did not come from woman; no, woman came from man; nor was man created for the sake of woman, but woman for the sake of man: and this is why it is right for a woman to wear on her head a sign of the authority over her, because of the angels. 1 Corinthians 11: 8-10.

As Green points out, “in the hierarchical relationship God-Jesus-Man-Woman … the woman does not have a direct relationship with God; it passes through Man.”[29] Basser agrees, and adds that “stating that the woman is (only) the reflection of man, Paul once again suggests her derived and secondary condition, and then he confirms this with an emphatic parallelism that the woman was created for and through man, and not vice versa (11: 8-9)”[30]

8) … women are to remain quiet in the assemblies, since they have no permission to speak: theirs is a subordinate part, as the Law itself says. 1 Corinthians 14: 34.

9) If there is anything they want to know, they should ask their husbands at home: it is shameful for a woman to speak in the assembly. 1 Corinthians 14: 35.

These two verses are a bit odd: they drop in with little context, if any. In some ancient documents, these two verses are not always placed in the same place within this epistle, although they are included in the same paragraph. Some researchers[31] thus hold the view that these verses originally were marginal notes written by someone, and that copyists later transcribed them into the text as was customary at that time.[32]

On the topic of how anti-feminine these words might be, Bassler states that the fact that the Church so readily accepted these verses as the words of Paul speaks volumes not only about the ambiguity of his position on women but also about the impact of the more explicit misogyny in the deutero-Pauline epistles.[33] Green adds that “Paul initiated a tendency that continues to condition Christianity.”[34]

What we have discussed so far seems to point towards a misogynistic view on women, however we must also point out that some of Paul’s positions on women appear to be ahead of his time and quite emancipatory. For instance, in the very same letter (1 Corinthians 7: 8.), we read:

10) To the unmarried and the widows I say that it is well for them to remain single as I do.

This verse is quite revolutionary as Paul indicates to women that celibacy is an option for them and they do not have to feel that they must marry; something that for the patriarchal society of that time seems now “surprisingly innovative.”[35]

Towey states that accusations of being anti-women “can be challenged by awareness of the social context of his time.”[36] Even more, he holds the view that “for Paul identity with Christ is the key. Racial, religious, gender and class differences are obliterated in Jesus …”[37]

And again: “Far from being misogynistic, he seems to have relied upon women to co-ordinate much of his missionary work (see Rom16:1-16), and despite his occasional demonstrations of self-importance, he is also aware of his limitations and reliance upon God”.

In the quote there is a reference to the epistle to the Romans, a letter which one and a half millennia later, in the hand of Martin Luther, changed the history of Christianity with the advent of Protestantism. Moving forward another four hundred years, a new commentary on this epistle brought popularity to the work of a Swiss pastor, Karl Barth, who became one of the most influential thinkers of 20th century. Indeed, he was once featured on the cover of the Time magazine.[38]

However the epistle itself has been extremely important since the beginning of Christianity, because in this letter, so peculiar and different from the others by him, Paul recorded “a systematic exposition of the gospel as he understood and proclaimed it”, as writes Bruce in a chapter titled “The Gospel According to Paul”.[39] This is the only letter that Paul addressed to a community that had not been founded by him.[40]

On first look it might seem that there is not much regarding gender in this long letter[41] (but 7: 1-6). However, at the end of the letter, in the sixteenth chapter, he places a section concerned with “greetings” in which ten females are included among the 29 people to be greeted on the arrival in Rome of his letter. And something more than just the name was mentioned regarding eight of the ten women.

There is nothing in the text to indicate that this chapter is not Paul’s, although some have argued that it was not because too many women are mentioned. This, however, is an extremely weak argument.[42]

The first woman mentioned is Phebe, and in some of the modern translations we cannot really understand her proper role it is translation as “a servant of the church which is at Cenchrea”[43]. Another translation refers to has as a “helper”.[44] In the older Italian translation the word “deaconess” was used. However in the (ancient) Greek text Phebe is called a “deacon”, in the masculine, in the Greek text “diaconos“,[45] which is a different role from that of a deaconess, which was established later in the Christian churches as someone who officiated in the baptism of women.

The expression “those who labour for the Lord’s work“, used by Paul, for example, in Thessalonians, 1 Timothy, is in fact a technical expression used to indicate those who are in charge of a Christian community.[46] This type of sentence, in Romans, is used for four women: Mary, Tryphaena, Tryphosa and Persis. And even more surprisingly, for the modern Catholic church, Paul writes that “Andronicus and Junia … are prominent among the apostles” (Romans 16: 7).

These titles and roles, in a church such as the Roman Catholic, which has relegated women to lesser responsibilities, are potentially quite explosive. The Anglican Communion, a church that retains apostolical and episcopal traditions, has already opened priesthood to women[47] and, some time later, even the episcopate.[48] Of course the protestant churches have opened to women’s ministry even earlier, whilst the Orthodox churches, similarly to the Roman Catholics, admit only men to priesthood.

Marinella Perroni too uses the epistle to the Romans to argue that Paul was not a misogynist because this letter shows in what high regard he held women both in the work of evangelization and preaching. In addition she reads the baptism formula, used in Galatians 3: 26-28 “nor is there male and female”, as fully inclusive of all human beings.[49] Francesco Lamendola states that it cannot be believed that a man, with such rich affection and such an intense sensitivity as Paul, could despise women; he admits, however, that the ‘apostle’ did share “some aspects of the dominant mentality of his time.”[50] Years before them, William Barclay paraphrased Romans 12: 5 with: “All Christians are one body in Christ” and then, went on to say “Because every Christian is in Christ, there can never be any barrier between those who are truly Christian.”[51]

We have briefly looked at the life of Paul in this essay and, using his texts, tried to understand something of what sort of person he was. In a piece of primary research we have seen that the hypothesis of his apparent desire for self-importance in one more quote derives from its translation into modern languages, where it gained a meaning that is absent from the ancient Latin translation or the original Greek text.

We have also seen that Paul’s views somewhat reflect those of others in his time (such as Peter’s). Moreover, some more contemporary considerations, such as equality of sexes and roles, were not his priorities: his aims were to establish Christian communities and to spread the new religion. Nonetheless, his work and influence have been so significant that some authors consider Paul the “inventor” of Christianity: “Jesus’ original preaching and example was not only recalled but was reinterpreted and adopted by Paul … to promote authentic Christian living in their several communities.”[52] However, this is not the most popular view held by scholars, as the majority of them think along the lines well put forward by Hunter: “Christianity stems from Jesus, not Paul; but Paul was foremost in grasping the true magnitude of his person and work…”[53]

As for him being anti-women or not, the evidence is not conclusive; as Pulcielli writes: “Paul can be read and interpreted—as in fact has happened—in opposite ways, both as one of the biggest detractors of the role and the ministry of woman, in the family and in the Church (and so as one of the causes of her discrimination in the society of Christian matrix), or as the first strong paladin of the equality between man and woman.” And he continues: “… the exegetic efforts have not being able to solve completely this obvious tension that emerges from his writings …”.[54]

If we remove those verses, or epistles, which most biblists do not now consider to have been actually written by Paul, the evidence appears to point both ways. Most modern theologians, particularly women, tend to lean towards highlighting the aspects that freed women in society and the roles given to women in the early communities, many founded by Paul.

Short essay by: Volfango Rizzi

Copyreader: Robert Burns (ceresetta@libero.it)

Thanks to Anna Urbani for having lent two essential texts for researching and writing this essay.

Note:

[1] Richards (2002): 26. Note: In this essay, the passages of the Bible are referenced within the text, whilst, to limit the number of words, other readings are referenced as footnotes. Further note: as some of the texts I have read are in the Italian language, the translation of such quotes is mine.

[2] Towey (2018): 140.

[3] Ibid: 144.

[4] Harris (2019): 22.

[5] Pascale (2019): 214. It can also be found as an online article in: https://www.storiauniversale.it/12-LA-MISOGINIA-DEL-CRISTIANESIMO-PAOLINO.htm

[6] Towey (2018): 141.

[7] Joseph A. Fitzmayer SJ in Hayes & Gearon (1998): 165.

[8] Towey (2018): 141.

[9] Harris (2019): 12 sets the year of birth at 5 AD, since Christ was born in around 7-6 BC, there are about 11 years difference. However some estimate that he was more likely born between 7 and 10 AD, in any case between 5 and 10 AD is what is usually considered more likely.

[10] Harris (2019) 12.

[11] See Fitzmayer SJ in Hayes & Gearon (1998): 166 and particularly note 3.

[12] Marinoni, Cassinotti & Airoldi: pp 17-18.

[13] Lemonnier (1981): 46-47.

[14] Richards (2002): 25. See also Harris (2019) at page 12.

[15] Towey (2018): 141. Bonelli (2019): 161 adds Philippians to the list of the “undisputed”, or less disputed, ones; this is normally considered Paul’s but a minority of researchers think that it may have been, in origin, two different letters later merged into one.

[16] Fitzmayer SJ in Hayes & Gearon (1998): 167.

[17] Ibid: 168.

[18] Harris (2019): 8.

[19] Fitzmayer SJ in Hayes & Gearon (1998): 170.

[20] Ibid: 173.

[21] We had to search for an English translation that helped to make the point clear, as it is easily understood in most of the other European languages such as Italian, Spanish and French but is not rendered in all the translations into English.

[22] In the Biblia Sacra Vulgata (the Vulgate translation) it reads: “… et quia memoriam nostri habetis bonam semper, desiderantes nos videre, sicut et nos quoque vos” not showing the emphasis found in translations into other languages. Similarly the text in ancient Greek does not differentiate between the degrees of either party’s desire to see the other.

[23] Joanna Dewey in Newsome & Ringe (1999): 195. See also Green (2009) pp 142-144.

[24] Green (2009): 73.

[25] Unione Cristiani Cattolici Razionali (2018).

[26] Bonelli(2019) : 243.

[27] E. Elisabeth Johnson in Newsome & Ringe (1999): 181.

[28] Harris (2019): 15-17.

[29] Green (2009): 135.

[30] Jouette M. Bassler in Newsome & Ringe (1999): 145.

[31] As Giancarlo Biguzzi, in Green (2009): 139.

[32] Jouette M. Bassler in Newsome & Ringe (1999): pp 146-147.

[33] Ibid: 148.

[34] Green (2009): 142.

[35] Jouette M. Bassler in Newsome & Ringe (1999): 140.

[36] Towey (2018): 152.

[37] Ibid.

[38] In the 20 April 1962 issue of Time magazine.

[39] Bruce (1977): 325.

[40] Bonelli (2019): 226.

[41] As mentioned by Green (2009): 5-6.

[42] Verrani (2014): lecture given in February 2014: it can be accessed on: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TsEdUHGFqzo

[43] Romans 16: 1. “a servant” is the most common translation; as in the following Bible translations: KJ21; ESV; ESVU; GNV; MEV; NET; NKJV; RGT and others.

[44] As in the EXB translation.

[45] In the New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition the translation “deacon” is used.

[46] Verrani (2014): lecture given in February 2014.

[47] In the 1970s in some Provinces. In England it was decided in 1992 and two years later the first woman was consecrated as presbyter.

[48] The first woman to become a bishop in the Anglican Communion was Barbara Harris in February 1989. In England the decision to allow women into the episcopate was taken in 2014 and one year later the first was ordained.

[49] Perroni, article in Vita Pastorale N. 1 January 2009.

[50] Lamendola (2019), online article.

[51] Barclay (1958): 124.

[52] Harris (2019): 74.

[53] Hunter (1966): 61.

[54] Pulcielli (2004): in the Introduction to this online article.

Short essay by: Volfango Rizzi

Copyreader: Robert Burns (ceresetta@libero.it)

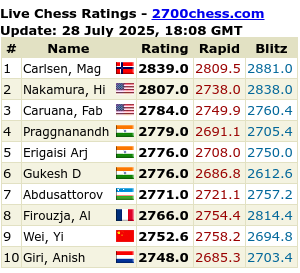

è una rivista bimestrale, che tratta esplicitamente di scacchi, rugby, pugilato e scacchi-pugilato.

Include, inoltre, la rubrica “altro”, in cui, in aggiunta a temi come l’aromaterapia e i giochi, viene offerta la

possibilità di sviluppare, in maniera coinvolgente, vari argomenti d’interesse generale.

è una rivista bimestrale, che tratta esplicitamente di scacchi, rugby, pugilato e scacchi-pugilato.

Include, inoltre, la rubrica “altro”, in cui, in aggiunta a temi come l’aromaterapia e i giochi, viene offerta la

possibilità di sviluppare, in maniera coinvolgente, vari argomenti d’interesse generale.

COMMENTI RECENTI